| Chapter Eight The Great Western

|

|

|

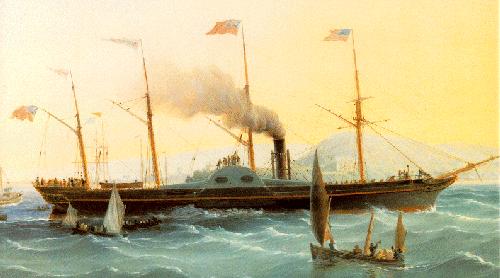

THE P.S. GREAT WESTERN

was Brunel's very first ship. It was built to connect

Bristol

with America. The Great Western was 236ft long and displaced 2300 tons

of water. Because of the space required for this type of transatlantic

ship, Brunel had to take into account the stresses put upon it by the

Atlantic. It was of conventional structural design with oak frames

forming the bottom and sides, and for extra strength, he added four

staggered rows of iron bolts running the entire length of the ship. The

hull was sheathed in copper below the waterline. The size of the engine

and the amount of fuel required was questioned by Dr. Lardner who said

there would not be enough room to carry the amount of coal needed for a

transatlantic crossing. On the 8th of April, 1838, the Great Western set

out for New York from Bristol. The ship arrived on the 23rd of of April,

with coal to spare. The story is not the same for a rival paddle

steamer, known as the Sirius, who left Cork, on the 5th of April and

arrived twelve hours before The Great Western. All the coal had been

used up, xand so had some of the fittings. The Great Western had

bettered the Sirius's time by almost four days. The Great Western became

the Queen of the Atlantic, regularly crossing between Bristol and New

York from 1838 to 1846. |

|

|

The Great Western Steamship

I intend to spend a few pages recalling the story

of the Great Western. The ship surely had a special place in the hearts of

Thomas and Ann Kilmartin. I referred to a book called "Ships at

Sea," by Duncan Hawes, published by Cromwell Co., Inc., and another

ship story called "The World of Model Ships," by Guy R.

Williams, published by G.P. Putnam & Sons, N.Y. In 1837, in England, the

successes of Francis Smith and Francis B. Ogden led to the widespread use of the

screw for ship propulsion. The power of a Helical blade in water had been proven

by the well known screw pump invented by Archimedes. Hence, later inventors had

no claim to originality. They could claim only the invention of methods to apply

the screw to ship propulsion, and there were many. In May, 1838, Francis Pettit

Smith obtained a patent for an Archimedes screw having two complete turns,

designed to be installed at the stern of the vessel, but at a considerable

distance forward of the vessel’s stern post. It was successfully tried on a

six ton launch called Francis Smith on Paddington Canal in February, 1837.

|

At a meeting of the Directors of the Great

Western Railway Company, in England, in October of 1835, it was jokingly

suggested that the Paddington, Bristol Railroad be extended to New York by means

of a steamship, to be named the Great Western. Although many at this time

believed it impossible to build a steamship with enough coal capacity for that

distance, the idea took hold. The Great Western Steamship Company was organized

in 1836. The Great Western was planned by the Chief Engineer of the railroad, I.

Ismael Kingdom Brunel. Her keel was laid in June of 1836 in the yard of Patterson and

Mercer in Wapping Bristol, England. As well

as having one of the most unusual middle names of all time, Brunel is

famous for his technological achievements in the field of engineering.

|

|

However, as well as having very broad interests, his most outstanding

feature was his all round ability within each of the endeavors he

undertook. If we consider his Great Western Railway, he designed the track

layout, the track itself, the rolling stock, the tunnels, the bridges, and

the ship to take passengers to the United States from Bristol at the end

of the line (the Great Western). He even designed the lamp-posts

for the stations, was a director of the station hotel at Paddington, and

when the going got tough, was not above getting down to doing some actual

digging on the line himself. He was truly a great all-round engineer.

Many of his greatest creations still exist

(Clifton Suspension Bridge, Tamar Bridge, Great Britain, etc.), and

are aesthetically pleasing as well as practical and long lasting. The

Great Eastern is perhaps his greatest work which no longer exists,

probably as it was too far ahead of its time.

|

|

The photo shows Brunel surrounded by the

chains

of the Great Eastern, shortly before his death.

|

Launched a year later, on Wednesday, July 9,

1837, The Great Western was built with great care. Particular attention was paid

to her longitudinal strength. Her accommodations were arranged for 128 first

class passengers, and 20 second class passengers. In an emergency an additional

100 could be carried. The crew consisted of 57 officers and men. The main saloon

measured 83 feet long by 34 feet at it’s widest point. It was decorated in the

Louis XIV style with 50 painted panels. The Great Western’s propelling

machinery was built by Messr. Maudsley & Sons, and Field & Blackwell,

and was installed in London. She was fitted with two side lever engines of 225

N.H.P. each with cylinders 73.5 inches in diameter by 7 feet.

Steam was generated at 5 P.S.I. pressure in four

iron return flue boilers. Each boiler had three furnaces. The coal bunker held

800 tons, and was arranged to carry water ballast when the coal was consumed.

The Great Western paddle wheels consisted of four separate blades arranged in

cylindrical curves so that they entered the water more quietly than radical

floats.

After suffering a minor fire, the Great Western

left Bristol for New York on Sunday, April 8, 1838, in a northwest gale with

only 7 passengers. Twenty five had signed up before the fire delayed sailing.

The engine was stopped only twice during the voyage. It was stopped for two

hours and again for twenty minutes to tighten various bolts on the paddle wheel.

She arrived in New York on the afternoon of

Monday, April 23, 1838, only to find she had been beaten by four hours by a ship

called " Sirius," whose trip was shortened by the owners of the

delayed British Queen. The Great Western actually made the faster passage,

taking 15 ¼ days to cover 2200 miles. She covered 354 more miles than the

Sirius who took 19 days for the trip.

She continued in service between Bristol and New

York until 1846. She was sold to Royal Mail Steam Packet Company Ltd., in 1847.

She ran for ten years from Southampton to the West Indies. In 1857, the Great

Western was bought by C.H. Marshall Company. She was converted into a sailing

ship by removing the coal and engines and adding four sails. The Great Western

traveled to New York from Liverpool for at least three more years. She carried

as many as 700 passengers in several lower decks. It took 26 days for her to

cross the Atlantic Ocean. I have a verified clipping from the New York Herald

Tribune, dated July 4th, 1857, of her arrival in New York.

Actual passenger list from the The Great Western,

November, 1860

I told this story because Thomas Kilmartin took

this sailing ship on April 21, 1859 from Liverpool and he arrived in New York on

May 17, 1859, taking 27 days. Reports during the voyage indicated sightings by

the Bark Evergreen, of Whiting, bound west on latitude 46.38, longitude 26.56 on

May 3, 1859. On May 3rd, a man named James Murray fell from the cross

jack and was killed. On May 9th, longitude 43, latitude 50.20, she

passed a large icebreaker. On May 14th she signaled the ship William

F. Schmidt bound east. The very important event relating to this ship was that

it was the same ship that Ann Kilmartin took in November 1860 from Liverpool to

New York. It seems that the movement to America by Thomas and Ann Kilmartin was

a strange coincidence or it was well planned.

Chapter 9

Top of Page

|